GK: So, returning now to subject matter: you mentioned that, in the past, you didn’t always feel drawn to a particular topic. It’s probably fair to say that most artists are striving for an artistic signature of sorts, or a thread that connects their projects. This might be a consistent visual language, whereas for others it’s often subject matter – a thematic territory they return to time and again. Where do you see yourself?

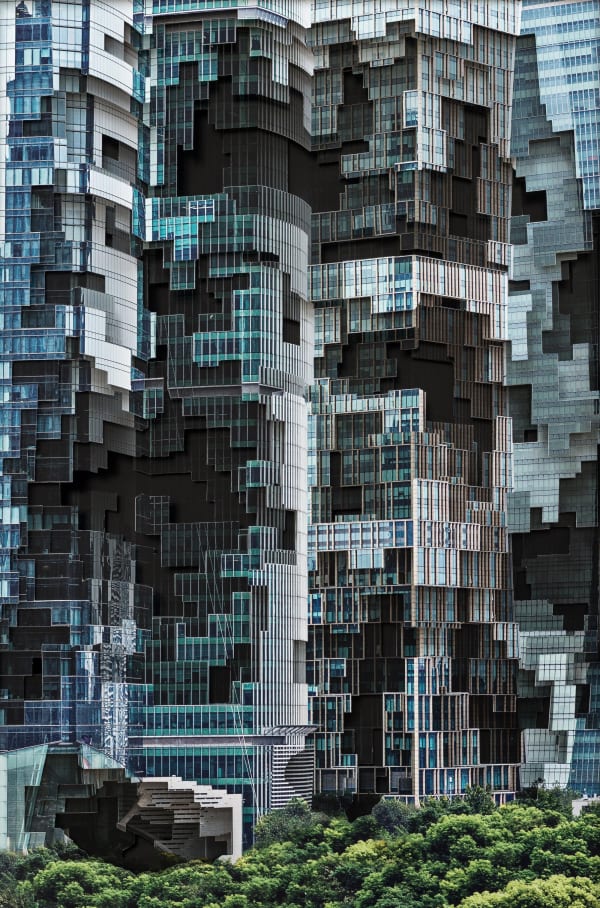

ML: It’s probably the former, in that my process carries me from one project to the next. But equally, when we look back we always see connections…or maybe we just make up a story whereby everything suddenly makes sense! In any case, I realise that many of my projects expresses this need to compress as much information as possible into an image. I could focus on anything, but something draws me to the urban landscape time and again, where there’s always a lot going on; a lot to convey. I used to tell myself I was doing it for stylistic reasons, but I think it’s probably a far more deep-rooted interest in urbanity.

Coming from a small village in the Black Forest, I think I’ve always been sensitive to the landscape, but I had these particularly visceral experiences of visiting huge cities for the first time. In Hong Kong and Istanbul, for instance, my brain just collapsed: it was totally overwhelming! I think my mind wasn’t used to that density of information – of sound, smell, colour. But it was significant, too.

More and more of humanity is being swallowed up by the city nowadays, and that’s my biography as well. The first half of my life was spent in the countryside, the other half in the city. So the technical aspects of my process are definitely a thread, but urbanity’s also there. I must say, though, I was super frustrated with this question of subject matter for many years; I often asked friends, ‘What should I do? I have this technique…but what theme should I work with?’. Looking for that subject definitely drove a lot of experimentation, but now I feel it’s started to emerge from the work organically.

GK: That’s interesting! And I recognise those pressures on artists nowadays. I’d actually wanted to ask you about this, because I saw you shared a tweet by the art critic Jerry Saltz a few weeks back, which reads:

"Dear all artists: never worry if your work is topical or political. Even if you’re painting landscapes and portraits, sewing abstract patterns, you are making your work in the present; the ‘deep content’ of the present is in what you are making. Your work is topical. Subject matter is not the sole determinant of your art. It is one of many weapons of mass destruction. Good subject matter can make good art and it can make bad art. Subject matter is fluid. Subject matter is a tool.”