French visual artist and photographer Vincent Fournier speaks to Effect Magazine about his work chronicling the mid-century Futurist and Brutalist structures of eastern Europe

We first encountered French visual artist Vincent Fournier at the Civilization exhibition in the Saatchi Gallery in London, where his photography reframed contemporary life as something unfamiliar and other, challenging us to look at it through entirely fresh eyes. Since then, we’ve discovered a deep hinterland of extraordinary work, from two books on Brasília’s modernist architecture to this year’s solo Uchronie exhibition at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris. All of it demonstrates the same unnerving talent of curating slices of life from our world and showing us quite how strange our world is.

Fournier’s interests range across modernism, science fiction, space, futurology and natural history. Aside from the latter, many of these are united by the idea of humanity’s striving for the future – both past attempts, as with Oscar Niemeyer’s utopian creation of Brazil’s new capital in the 1960s; or with contemporary industry and space programmes.

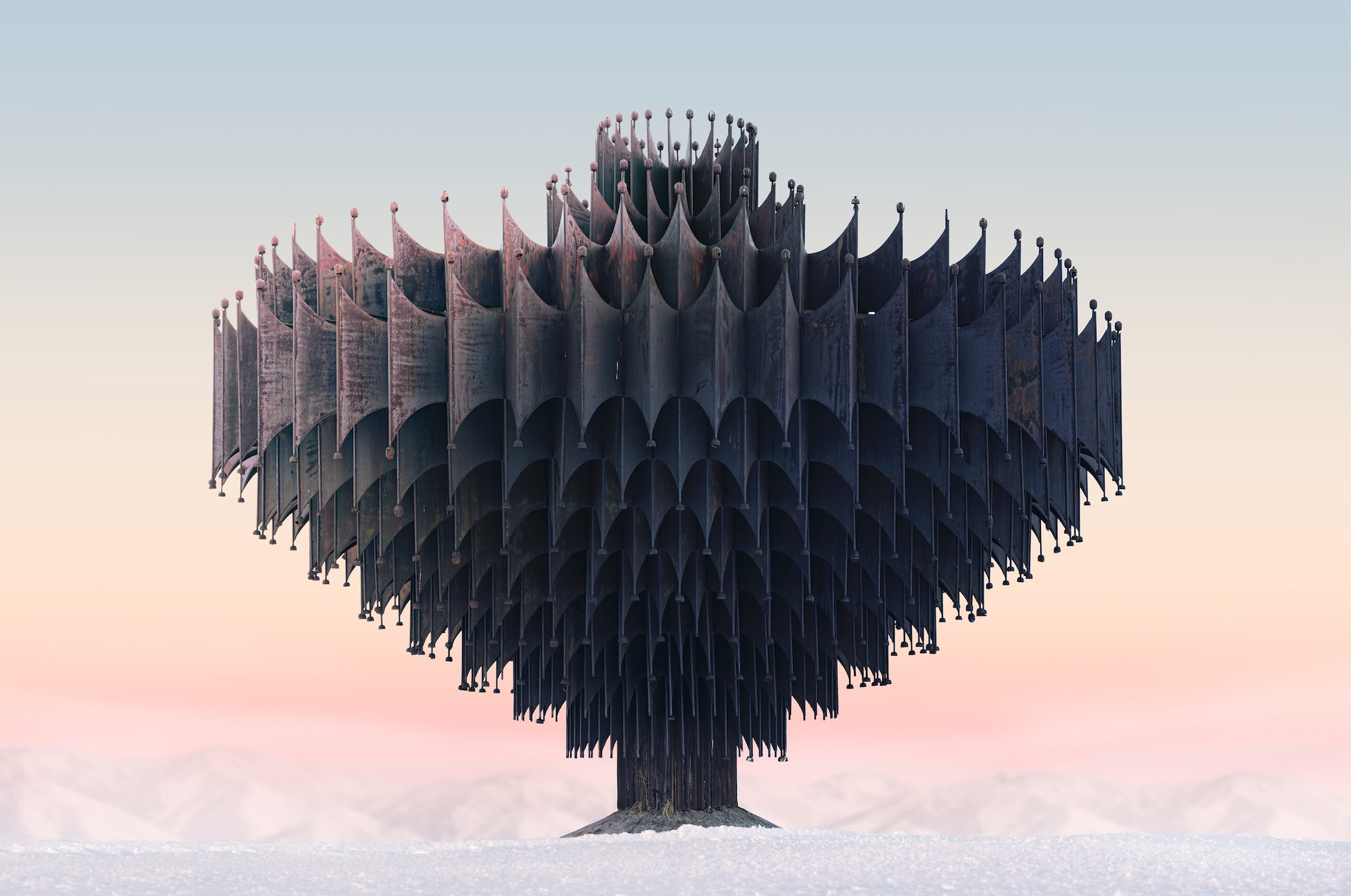

One of the most Fournier’s arresting bodies of work is Kosmic Memories – an extraordinary photographic chronicle of communist-era Brutalist and Space Age architecture from the ex-Soviet Union, central and eastern Europe. They are not just remarkable buildings and monuments – they are brilliant portrayals that, by stripping out saturated colour and layering them in snow, enable us to see these past attempts at futurism in all their strangeness.

We sat down with the Ouagadougou-born Frenchman to learn more about his life and work.

Here’s what he had to say:

How would you describe your photographic and artistic philosophy?

It’s a combination of opposite elements – “the secret harmony of opposing forces”. I like to play with the perception of time, mixing the future with the past. My inspiration comes from my childhood in the 1980s – movies, documentaries and TV series, speculative novels – which mixed and superimposed in my memory, with all the dreams of the future we have at this time.

"Kosmic Memories reveals extraordinary architectures, veritable totems of future civilization, erected as signs of a possible elsewhere." - Vincent Fournier

The brutalist structures in Kosmic Memories – and the modernist utopia of Brasília, which you have also documented, present past attempts to reach for the future. Is this what attracted you to these subjects?

Yes, indeed. Their forms testify to the same breath: the invention of a future impregnated with science fiction. My interest for those architectures, the city of Brasília and the Kosmic Memories sculptures, comes from a mixture of fascination and nostalgia for the stories and representations of the future.

They both are modernist temples fossilised in a utopian future, just like a time capsule. The Kosmic Memories series reveals extraordinary architectures, veritable totems of future civilization, erected as signs of a possible elsewhere.

How have you explored this with your work?

My work explores our imagination of the future – that of yesterday and that which we imagine for tomorrow. This architecture, erected as signs of a possible elsewhere, was perfect for this body of work.

Which structures in Kosmic Memories made the greatest impression on you?

Maybe the Kozara, Kosmic Memories, 2020. The size is very impressive.

The snow enhances the feeling of dislocation and strangeness in Kosmic Memories. When did you decide to take this approach?

Since the beginning of this project, the snow was definitely part of the story as a main character, with the very low light as well, from sunset or sunrise. I wanted to give this feeling – both romantic and nostalgic – and to celebrate this beauty.

The famous artist Enki Bilal, who inspired me a lot as a kid, and still does now, wrote about the work in Kosmic Memories: “Where did this come from? Where did it come from? What’s inside it? Where and when will it go again? Who, of the snow that holds back or the sky that calls (reminds?) will have the last word? Vincent Fournier’s eye creates a link with the unfathomable mystery of the endless universe. And he questions: where did it come from? When will it start again? Or not.”

What are the key technical considerations for capturing architecture?

No rules, all rules. It’s a matter of make the best configuration with your idea and the way to get it.

The Saatchi Gallery’s Civilization exhibition – which features your work – seeks to capture the mood of our epoch. How would you describe that current mood?

Our era is at a turning point. We are made of the dreams of the future from the mid-last century. However, those dreams, that was built by and with the help of mainstream industries in order to sell their products, are no longer fitting our civilisation.

Our planet just can’t follow those dreams anymore. We have to find new imaginary worlds. I don’t think we have to destroy those dreams – it wouldn’t work, anyway – but we need to propose new ones. The way we live now has to change. For the better, also, because we are losing our sense of sharing that is essential for a civilisation. It’s not only about empathy but a question of survival. The future will be whatever we are doing now, in the present, so we have to do the right things in the here and now.