Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, known better as Inez & Vinoodh, real-life partners and professional photography duo, built their career in the gray space between fashion pictures and fine art photography. This wasn’t by accident. As they tell Derek Blasberg, they used their educational foundation in historical Dutch painting to inform their work with some of the biggest names in contemporary fashion, including Chanel campaigns, Lady Gaga music videos, and editorials in editions of Vogue from around the world.

DEREK BLASBERG (DB): Fashion and art isn’t a new idea, of course. We know the big references, like Coco Chanel asking Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau to create sets, or Gianni Versace incorporating Andy Warhol’s imagery into his designs.

INEZ VAN LAMSWEERDE (IVL): The two disciplines have always informed each other and it’s always been an inspiration to go back and forth. There’s this cross-pollination; ultimately, you’re dealing with expressing the human condition.

VINOODH MATADIN (VM): We grew up going to Amsterdam’s museums, like the Rijksmuseum, every week. It was part of our education and it was built into the primary-school curriculum. It’s the basis of our knowledge of art.

IVL: From the influence of Dutch painting on composition to the colors of Van Gogh. The Dutch are proud of that heritage, and of the importance of the collections in the museums in Amsterdam and in all of Holland. It’s instilled in you at an early age.

Derek Blasberg is a writer, editor, and New York Times best-selling author. In addition to being the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly, he is the head of fashion and beauty for YouTube. He has been with Gagosian since 2014.

Since the early 1990s Inez and Vinoodh have created groundbreaking editorial photography for such publications as V Magazine, the New York Times Magazine, W Magazine, and American, British, French, and Italian Vogue. Their innovative approach, pairing visual seduction with provocative narratives, has also featured in campaigns and films for fashion houses including Balenciaga, Calvin Klein, Chanel, Dior, Gucci, and Valentino.

DB: When you were young, did you guys know you’d work in the arts in some capacity? Was that the plan?

VM: Yes.

IVL: Yes. My mom was a fashion journalist and later taught fashion design, fashion history, drawing, and painting in different art schools and academies. She was always around fashion and showed me everything. My whole life, she was always in Paris for fashion week—she saw Dior’s New Look show right after the war, we’d always have French Vogue at the house. It informed my ideas about how women should look and behave. I grew up with the pictures of Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, that whole generation. That was the imagery I was fed. There was never an alternative.

DB: When did you pick up your first camera?

IVL: 1984.

DB: Had you thought about being a photographer before that?

IVL: No, because the school where we met was a fashion-design school. I thought I was going to be a designer or an illustrator, but it turned out I kept taking pictures of my friends that looked great, and I’d style them and compose the photographs. Then, I was modeling in a show in Paris with Rineke Dijkstra, this phenomenal photographer, and she said to me, You should be taking pictures. She told me to quit even thinking about the design stuff, and I believed her. I applied to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, where she was studying, and I got in.

DB: Is that where you met Vinoodh?

IVL: We first met when I was a model for his fashion brand.

DB: That’s right, you were a fashion designer before you were a photographer. When did you first pick up a camera?

VM: When I was sixteen, but I never thought I’d be a photographer. I always thought I’d be a fashion designer too. I remember seeing a book of [Yves] Saint Laurent’s exhibition [at the Metropolitan Museum of Art] in Manhattan, which was curated by Diana Vreeland, and I was like, This is it. This is fashion and art together, and this is incredible. That was my spark to go into fashion.

Cindy Sherman - The Gentlewoman, 2019 © Inez & Vinoodh

DB: For many people, Vreeland was the one who put fashion into an academic context. She invented the world of fashion exhibitions we see so much of today.

VM: That was a revolutionary show, especially for when it happened, in the early 1980s. She had so many incredible ideas and I loved them. Then, when I did my first fashion show, I asked several art people to be my models.

DB: And that’s when you met?

IVL: When he did his first collection, he asked me to take the pictures for the invitation. We worked together on the casting, the styling, all of it.

VM: And we were like, Oh my God, we have so much in common.

IVL: That’s how the whole thing started. It was 1986.

DB: But how did you go from that collaboration to becoming artists together, and abandoning your fashion line?

VM: When we went to New York in 1992 for PS1.

IVL: We were artists in residence at PS1 and Vinoodh gave up his whole designing thing.

DB: Was that hard to do?

VM: No, because I wanted to be with Inez. I felt like, Let’s go to New York, let’s do this!

IVL: And very quickly, we just started to make everything together.

VM: At first, Inez was working on my things, and I was working on her things, and it was separate credits. Then we were like, Let’s just do it all together.

Freja and Raquel with Tourist by Duane Hanson, 2009 © Inez & Vinoodh

DB: In many ways it’s become easier now to be fluid with working relationships and even genres. There was a moment when you were a photographer, or you were an artist, or you were a model, or you were a designer. Now, you guys are artists. Sterling Ruby is now a fashion designer. Virgil Abloh is all over the map. There are people who do many things now.

IVL: I clearly remember being shocked in the early 1990s when all of a sudden artists started turning up in Vogue’s best-dressed lists. I was like, What’s going on? Why are they now part of this? For so long, people thought it was selling out or a dirty secret. Then, slowly, that started to change, and thank God all those lines are blurred now.

VM: When we started, it was hard because the fashion world said we were artists and the art world said we were too fashion. I think that’s why we now have this feeling of not caring what you call us.

IVL: We deliberately try to stay on that middle line between the two worlds. That’s always been the part that’s the most interesting for us.

VM: And keeps us independent.

IVL: We feel independence in the images we’re making. We’re questioning both sides and embracing both sides, all at once. When a photograph has a clothing credit underneath it, it’s a fashion picture, and when the name of the person in it is mentioned, it’s a portrait. When I give it a cynical title, it’s an art piece. For us, the context is interesting, and playing with the notion of it. Especially when we started, there was irreverence. When we began shooting for Vogue, we felt like it was a joke, an experiment. We were thinking, Let’s see what this feels like. When we were shooting for The Face in the beginning, we wanted to get those big brands in but as a joke, as an experiment, because we didn’t take it seriously.

VM: The magazine told us, You don’t have to do that, we’re The Face, we don’t have advertisers.

IVL: And we explained to them that we liked that. We liked the connotation of what it said. We like to subvert from the inside. At some point we said to each other, How long are we going to stay cynical? Does it feel like we need to embrace both worlds more, and actually go fully into both worlds at the same time?

VM: At that moment, Yohji Yamamoto asked us to do his campaign. That was like an art form for us, because we had total freedom to do what we wanted. We had no discussion with the designer, we just did the campaign. In those days that took two to three months from start to finish. It was a long, slow process.

IVL: We’d see the show, react to it—

VM: And then we’d see Yamamoto’s reaction to our reaction. It became an entire dialogue.

Hannelore Post Grunge - Yohji Yamamoto Campaign, 1999 © Inez & Vinoodh

DB: What I liked about your pictures in The Face was that they seemed to take things that everyone else thought was precious, like couture dresses, and treat them unpreciously.

IVL: That’s because we felt like outsiders looking at that world. I remember clearly when we started shooting for Vogue, our favorite thing to do was sit in the office of the bookings director and just observe everyone. We were absorbing, learning, trying to understand that American Vogue woman.

VM: Where does she come from? And who makes these rules that they all follow? Why are they not free?

IVL: It was definitely educational. Also, in a good way, we didn’t realize what a big deal it was to work for Vogue. We were just laughing, and thinking, What’s going on?

DB: Your exposure to all this fashion, drama, excitement, rules—did that inform the way you created your pictures?

IVL: You start to learn more about stereotypes.

DB: By stereotypes you mean trends. I never realized that they’re the same thing!

IVL: Yes, exactly. Status symbols! That’s the language of clothes. You’re expressing through clothes. Today, for example, you’re an intellectual because you’re wearing a New Yorker T-shirt.

DB: Wow! For the record, this T-shirt came with the subscription!

IVL: That’s what I mean. You have a subscription. You read it. Everything is a status symbol.

VM: Even if you’re not in fashion, it’s a statement.

IVL: Every person who wakes up in the morning has to ask, on some level, Who do I want to be today? Do I have a meeting, or am I on mom duty, or am I trying to impress a date?

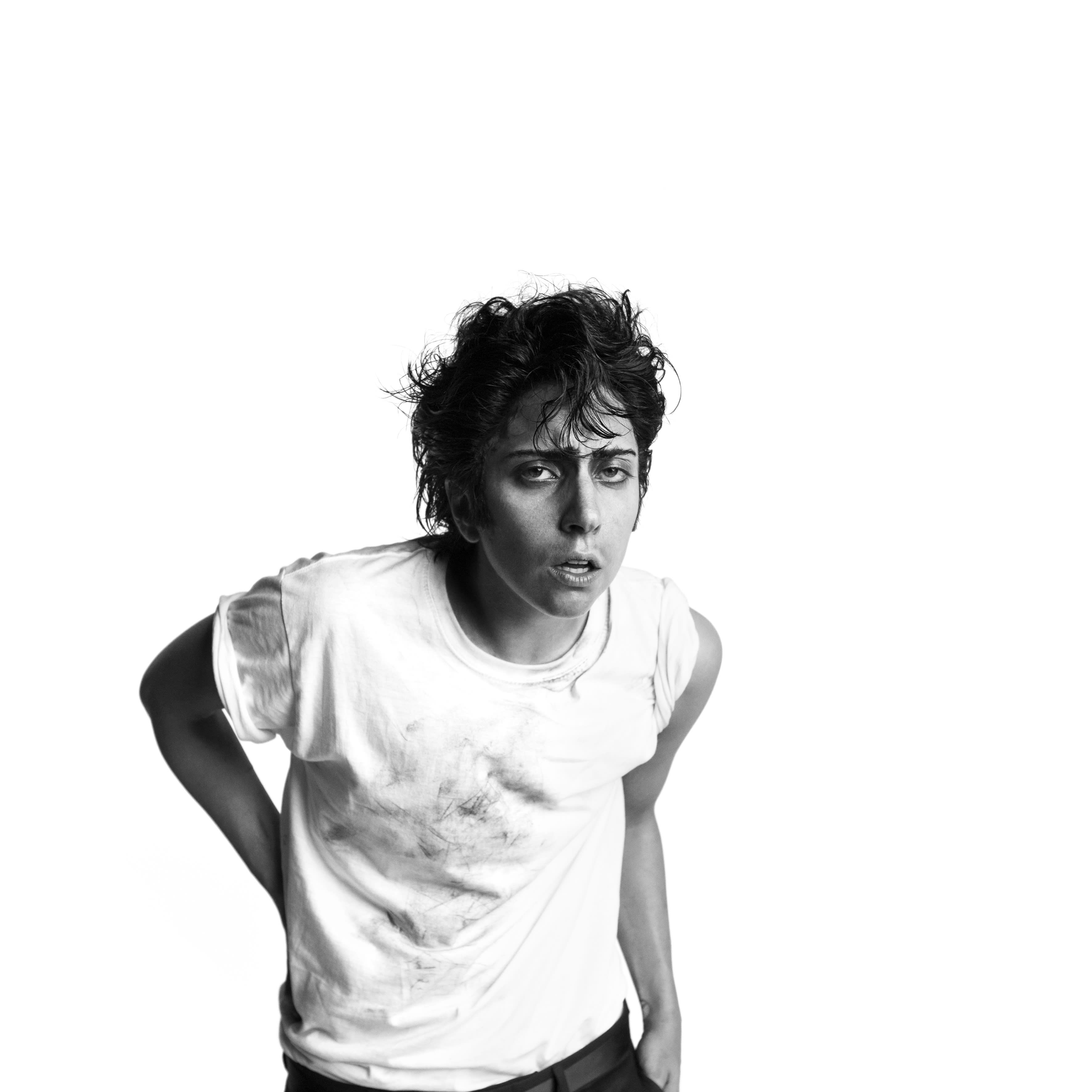

Lady Gaga / Jo Calderone - You & I, 2011 © Inez & Vinoodh