-

-

George H. King: Shall we kick off with Berlin?Eva Stenram: Sure.GK: So you’re originally from Sweden, but you spent many years in London, and then moved on to Berlin a few years back – in this kind of post-Brexit, pre-pandemic window. What inspired that move?ES: So, as we all know, the British population voted to leave the European Union in 2016, and as we also know, it really changed the entire country – the mood, the future outlook and the political direction. As a product of EU freedom of movement myself, it was a depressing time. It seemed unbelievable.GK: Yeah, it’s still such a nightmare!ES: And I’m sure many people had the same reaction. We decided to move in 2018, to try out life in a different European city. Berlin was in many ways an easy choice – with its broad and interesting cultural life and fairly international art scene. We also had some good friends here to guide us through the moving process.

-

"I feel happy with the decision, even though it wasn’t an easy step after having spent more than 20 years in London."

-

-

GK: Right. And how has that move – if at all – influenced your work? I was thinking of New Meridians, one your ongoing projects that you began after your move to Berlin. These manipulated images of the landscape felt quite new to me, or distinct from the works I first knew you by. Is that fair?ES: Yes, New Meridians is definitely quite different from my best-known works, but it fits in well with my overall practice – particularly with projects like Per Pulverem Ad Astra or Oblique.The project was originally a response to the 2019 European elections – the first since Brexit – when there was a danger that Europe would experience a big shift towards various populist far-right political parties. I started collecting issues of an old West German travel magazine called Merian from the late 1950s: around the time of the Treaty of Rome, when the EEC was founded. The magazines featured images of highly idealised landscapes – designed to sell travel of course – from these core European countries like France, Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands.I started simply by scanning the images in, then overlaying them with various different markings. Lines, arrows, deletions, it’s not really clear what the interventions mean, but they suggest many things, like the movement of people or goods, borders, lines of communication, or different strategies for the usage of the landscape, perhaps. They’re like some kind of planning documents. Do they represent some kind of Utopian moment in which an orderly future is being planned or do they represent something darker – showing fractures, divisions and censored histories? During the pandemic the images acquired new associations, and with another war taking place in Europe now, even more resonances come into play.

-

GK: I hadn’t yet made that connection with Ukraine, but the resonance is clear. It feels as if there’s something more overtly political about this work, but this idea of mediating an image, that’s a constant, right?ES: Yes, true! So, to go back to the beginning of the process, all my work starts with the discovery of a set of found images that somehow draw me in and fascinate me. But beyond that impulse, there’s also my desire to have an interaction with the image, to investigate it, and perhaps to underline and enhance certain qualities it carries. Or even to subvert it. So there’s an interaction there – and the resulting images thereby contain an insertion of me, of what’s going on around me, or maybe just what’s going on generally in society.

-

"So, as I mediate the image, the older found image is brought into play with the present moment."

-

Split, 2016

-

GK: And where did this impulse come from to work largely with found photography?ES: I only really became interested in photography when I discovered Photoshop, and I initially loved how the manipulated image could bring together different moments of time and space. With photography, you always have these folds of time and space – between the present viewer and the moment the photograph was taken. But I liked the idea that you could add extra folds within the image itself.For my first photographic project after this discovery of Photoshop, I investigated my parents’ family album. I’d always been fascinated by photos of my parents from before I was born, and I wanted to interact with that era somehow. I found myself asking questions like, ‘What would it have been like if I’d met my parents when they were in their 20s? Would we be friends? Would we fall in love? Or fall out?’. So it’s about that unknown period in your parents’ lives.

-

"The connection between photography and fantasy is already evident in these early projects, but it’s been teased out further in the work I’ve done since."

-

GK: When you’re doing all this work with found imagery, presumably you’ve amassed quite a collection of stuff?ES: My collecting is actually quite targeted; I don’t usually collect random images in the hope that I’ll use them someday, although, I also have some image collections that I haven’t used in my work. A huge stack of American gun magazines from the 60s, for instance. But the main body of material I have is pinup imagery, mostly from the 60s: from magazines, but also negatives and slides from photographic archives.In most cases, I have a specific purpose in mind, and I collect a certain type of image. Nevertheless, these images might turn out to serve several purposes: I sometimes use the same image in different ways within and between projects.Having said that my collecting is targeted, I’m still interested in the surrealist chance encounter, so I do also randomly look for images on eBay or in secondhand bookshops, to see what it might trigger.

-

-

GK: Is there something about the 1960s, from where a lot of this material seems to originate, that you’re particularly drawn to?ES: I don’t know if I can properly pinpoint it. I can say some things that I find really interesting about the era: that it was a time of political upheaval, increased sexual freedom, but equally a very conservative time. It’s also the time when my parents were young. And I like the aesthetics of the images.As photography is now more of a flow of quick communication, perhaps I’m also nostalgic for a time when it seemed that more attention was paid to single still images. But for me it’s also important to find ways for these found images to speak about the present - I don’t want them to remain stuck in the past.GK: And what, for you, does working with found material mean for authorship?ES: I feel like it’s really important to change the meaning of the image; this can be done through manipulation, cropping or changing its context. But a transformation absolutely has to take place -there needs to be a reason for the new image to exist.Generally I know very little or nothing about the original photograph and the original photographer. But I hope that the original photographer, whoever it might be, would appreciate my reworking! I think of photography as an interactive medium, and of photographs as being in flux or changeable over time. They’re not merely static things – they’re constantly being re-presented, re-contextualised, re-purposed. The work is really about me being a viewer of images (rather than a producer) and I try to figure out how we look at images and interact with them. I then end up producing a new image from the old, with a new set of meanings.

-

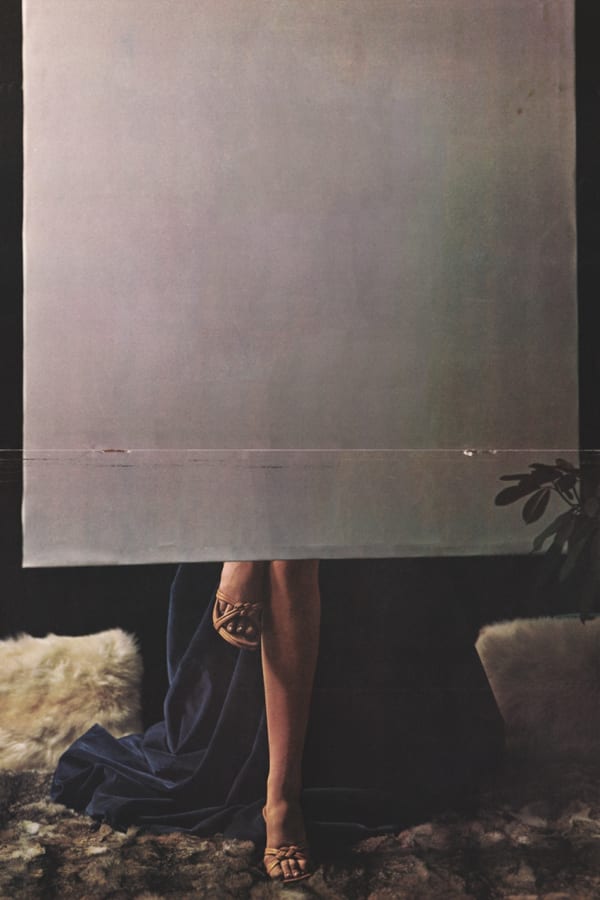

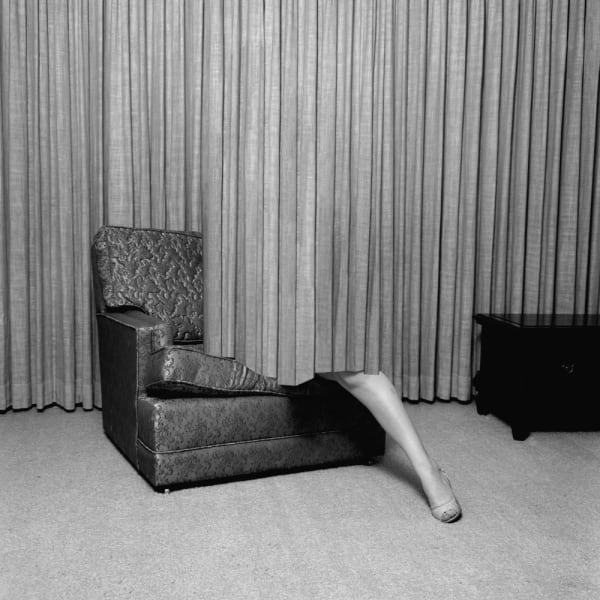

GK: Earlier I touched upon the works for which I know you best, and here I was thinking particularly about the Drape works, as well as the later Oblique series. They’re quite different in appearance, but both depict and re-invent human subjects in some way. Can you describe these projects in brief?ES: I started working on Drape about ten years ago, when I first came across one of these 1950s or 60s pinup images by chance. I had been experimenting with using a background drape to cover up parts of the original image, and suddenly I found this intriguing pinup image with a drape in it and the project kind of clicked into place. I searched for similar images – with a model posing in front of a curtain or drape – and then I digitally extended the fabric to partially obscure the model. The effect seemed to heighten the viewer’s curiosity, but it also made for quite a strange image where the background and foreground exchanged places in the image. The original focus disappeared, and the woman appeared almost trapped within her domestic settings.Then there was another project, Parts, which used similar source material, but the effect is quite different. Instead of covering up the model in the image with the drape, I erased most of the model’s body by just copying and pasting other areas of the image over it. So what remains is just one leg, in exactly the place it was in the original image, though the rest of the model’s body has been camouflaged – swallowed up – in the image. So where Drape plays with voyeurism and curiosity, Parts is more macabre, absurd and uncanny. It’s very theatrical, and I think the erotic effect of the original image is totally turned on its head.Oblique began when I started noticing these small sport sections in the pinup magazines – which led me to buy some dedicated sports magazines from the same era. Here, the body was again depicted in an idealised form, in a very different way, and the inclusion of the male body was much more commonplace. I decided to rephotograph very small sections of the images, to scrutinise the details of the magazine pictures forensically. I was sometimes looking for a kind of tenderness or eroticism in these images, but I became more interested in isolating details, then using a system of markings and annotations to play with the idea that the images had a kind of code, or some significance to them…it was a way of drawing attention to something, but what exactly remains unsure.

-

GK: Is there some kind of statement you want to make there?ES: Between those projects there’s a general interest in these erotic moments in photography, and what captivates me there is how the boundaries of the photograph get broken down. In Drape and Parts particularly, there’s a direct sense of immersion into the photograph. This happens with all photography to some extent, but it’s made more explicit in erotic photography. As our imagination and our desires and our thoughts about touch activate the image, it almost breaks down those boundaries, and we lose ourselves in it. And that’s a kind of general thing that interests me in my work: this duality of having visual control of the image and losing ourselves within it. This is also what my works that utilise fabric, such as Vanishing Point and Split, attempt to do.One of the inspirations for Oblique was the Antonioni film Blowup. This question of what’s revealed when you start looking further and closer into an image. It’s almost a kind of over-interpretive, slightly paranoid state of mind that I was interested in there.

-

-

GK: So the way you mediate images is of course designed to incite a new way of looking at them, but that’s heightened when you’re dealing with a type of photography that was intended to elicit a particular reaction?ES: Yes, Drape, Parts and Oblique are all quite different projects, and the method of manipulation and changes that I have put the original images through will indeed elicit quite different reactions and readings. But of course the source image also contains its original meaning and that will interact with any changes that I make to it.GK: You mentioned discovering Photoshop as being very significant for you. Would you say, then, that there’s a tension in your work between the analogue images you’re working with and the digital tools with which you’re disrupting them? What effect does that have?ES: I think I’m looking to achieve a certain timelessness, or at least a confusion of time in the images. I want the digital work to be visible in the image, so that my process is visible as well. So the reading of the image for the viewer includes knowing that the image has been tampered with. And I guess we haven’t really spoken about nostalgia, but sometimes I feel like the digital disruptions move the image away from an overly nostalgic context.

GK: So the nostalgic feeling is something you want to avoid?

ES: I don’t know about avoid. I just want the images to reach a state where they’re not so anchored in one time and space. It’s about this bridging over from the past into my present. Regarding nostalgia, I think all photography’s nostalgic; even a photograph taken five minutes ago. That’s the condition of photography, and it’s part of its power.

-

"And I guess we haven’t really spoken about nostalgia, but sometimes I feel like the digital disruptions move the image away from an overly nostalgic context."

-

Sideboard Survey, 2021

Installation view at Fotografisk Center, Denmark -

For more information on available edtions and prices, please contact the gallery via phone at: +31 (0)20-5306005 or via email at info@theravestijngallery.com

-

-

MODES OF FABRICATION

August 2, 2021ARTISTS HAVE LONG SOUGHT INSPIRATION IN FOUND PHOTOS. WE CONSIDER THE ETHICAL AND AESTHETIC IMPLICATIONS OF COLLAGE IN AN AGE OF VISUAL ABUNDANCE. On an unspecified date in the 1960s,... -

Photographic Pastiches of Vintage Erotica | Eva Stenram

September 23, 2016Detail from Vanishing Point, 2016 © Eva Strenram / Courtesy of The Ravestijn Gallery Artist Eva Stenram recontextualises the pin-up imagery she encounters to reveal new photographic tensions, as her... -

1000 Words | Eva Stenram

July 3, 2012One of the highlights of my visits to Les Rencontres d'Arles is the section of the festival dedicated to the Discovery Award exhibitions, housed in the giant, dusty, former train...

-

-

During Paris Photo 2022 The Ravestijn Gallery presents 5 artists in the online viewing room: Inez & Vinoodh (NL/US), KYoung (UK), Theis Wendt (DK), Tereza Zelenkova (CZ), and Eva Stenram (SE).For this occasion we asked George King to interview Eva Stenram for our 'In Conversation With' series.Eva Stenram's photographic practice brings together analogical archival material and digital manipulation, sifting through past and present artifacts and re-interpreting the imagery she encounters.